Keenan Viney

Introduction

The deep recession of 2008 was touched off by financial crisis. In the years before the credit crunch, banks across the globe had been engineering and trading new types of financial derivatives. One of these new derivatives was the Credit Default Swap (CDS). Put simply, these were insurance policies against default on other derivates.

The CDSs were perceived as having quite low risk because the probability of the underlying derivatives defaulting was assumed to be quite low. However, a sudden rash of mortgage defaults in the United States caused some of the CDS derivatives to become active. Unfortunately, mortgage defaults and the CDSs were systemically related and this lead to cascading failures. Banks that held lots of the now toxic CDSs were stricken and, in the case of the English bank North Rock, had depositors queuing in a resulting bank run.

The banks that were in the greatest trouble needed to borrow from other banks in order to satisfy the increase demands of their depositors. The few healthy lenders knew that the banks borrowing their funds might not pay them back, so the lenders did not lend, and the credit market dried up. This paper investigates the inter-bank market for credit in order to address the role of information and regulation. By the end of this paper it will be possible to put forward practical solutions which will decrease the likelihood of such an event happening again.

The majority of economic theory is done in the environment of full information. As prices and counterparty risk becomes more opaque, markets begin to behave in very unusual ways. In Akerlof’s (1970) pioneering work he uses the market for used cars as an example of asymmetric information. Much like bank health, the quality of a car is uncertain to the counterparty, under uncertainty with large differences in quality, the market may not function at all.

The information problem is applicable to inter-bank lending, also known as the overnight market. When a bank lends money, it does not have full knowledge about the health of the borrowing bank. In times when many banks are unstable, the lack of information causes banks to cease lending altogether. The problem of inadequate counter-party information was seen firsthand during the financial crisis in 2008. The United States Federal Reserve was in constant communication with the major banks and held meetings to try and increase the amount of information available in the banking sector. The Federal Reserve was also actively assessing bank health through stress testing which involved gathering detailed information about bank balance sheets.

The banks that held CDS derivatives generally did so off of their balance sheet. This meant that the risky liabilities were not accounted for when deciding what level of reserves to hold. Had CDSs been included in bank liabilities, banks would have held higher reserve ratios which is the amount of money held in vault cash to serve demand deposits. In Canada, reserve ratios are unregulated and the same is true in the United States. When the financial crisis hit, banks wanted to hold more reserves to brace against the possibility of a bank run. Banks with, what in normal circumstances, would be excess reserves were unwilling to lend. Of course had reserve ratios been mandated, banks would have been less impacted by their CDSs turning toxic and less vulnerable to bank runs.

Economic Model

The interbank lending market is much more complicated than the computational model used in this paper. For instance, the Canadian overnight market has two different settlement systems which effectively creates a two-level market; for small and large capital transfers. What this computational model does achieve, is simplicity without losing key aspects which maintain external consistency.

In day to day operations banks are experiencing deposits and withdrawals that randomly redistribute reserves across the banking sector. At the end of each day those banks that have excess reserves are willing to lend their surplus to banks that have low reserves. This market generally functions quite smoothly because large banks tend to be quite stable and the loans are extremely short term. Problems begin to arise when there is the perception of instability in the banking sector. Depositors want to withdraw more cash than usual, either to cover their own losses on the worsening financial market or because they fear the bank will collapse. Having to provide more demand deposits means that banks want to have more reserve cash on hand. This means that banks that have excess reserves will be unwilling to lend, forgoing interest to bolster their own reserves.

An even more important process may be underlying freeze up of interbank lending beyond the higher desired reserve levels. This is the problem of asymmetric information between banks. In the recent financial crisis a handful of banks got into trouble when off balance sheet derivates went bad. These troubled banks needed additional reserves while in the process of writing down these liabilities. The problem was that the troubled banks were made unstable enough that the risk of default in the overnight markets increased. On might suppose that interest rates could simply rise enough so that banks with excess reserves would again be induced to lend.

What Stiglitz and Weiss show is that no interest rate could be high enough to induce lending. This is because the only banks that would be willing to pay high interest rates would be the banks that are most likely to default (1981). This situation could be averted if banks had full information about their counterparties. Under full information banks of good health could continue trading with one another and would not be affected by the instability of other banks. Now it should be noted that the following computational model will not have all the facets that have just been described. A cursory read of the Stiglitz and Weiss paper (Ibid.) will reveal the necessary use of dynamic modeling that would not yield different predictions than this paper and would be far more computationally costly.

Computational Model

This paper utilizes the seventh version of Matlab to simulate the market for overnight funds in different specifications. Once the initial model was created and running, it was possible to use plots to visualize the outcome after changing different variables. The fact that Matlab is very good at manipulating matrixes meant that it was possible to get an output that showed the final stated of all banks at the terminus of the run.

One of the advantages of using Matlab rather than showing then modeling this market with dynamic equations is that it is far easier to parameterize the model. While some academic papers can provide similar results they cannot give any indications about how the number of banks or a variety of information specifications would affect their results. By using a computational model, this paper confronts much of the systems complexity head on and in doings so can offer a broader range of policy alternatives.

Because the coding of this model does not make its functioning completely apparent, what follows is brief statement on how results are derived. The first lines that run are setting initial values; for the number of banks, the number of iterations of the main loop, reserve shock size, bank health, and whether a bank can view the health of another bank. Initially, all banks start with the same level of reserves. A random shock of a given size is applied to a pair of banks and it offsets in such a way that the total reserves of the sector is constant. Banks are then sorted into groups of lenders and borrowers. This sorting happens in each period of the model and is dependent on whether a given banks reserves are more or less than one. Those banks with reserves equal to one have no reason to lend or borrow and so are left out of the groups. The next section of the main loop houses the outcome and consequences of the loan decision. First a lender is selected and makes a lending choice based on whether they have information about the borrowing bank, and if the lender does have information it will decide to loan based on the health of the borrowing bank. If a loan is made the reserves between the two banks will be averaged, this might seem somewhat unrealistic but this mechanism mirrors the convergence of reserves to their desired level that we see in real life. Once the loan has been made, the borrower will only repay if the bank is healthy (below a specified health limit). If the borrower defaults on the loan, it will make the lending bank less healthy. Finally, the reserves throughout the iterations can be plotted and final reserves can be tabulated.

Experiments

Three experiments will be conducted to explore the consequences of different specifications. As such, treatments will be conducted ceteris paribus so as not to confound variable relationships. Since this paper will make policy suggestions the three experiments will try to correct market failure.

Experiment 1 shows the effect of information on the interbank lending market. There are two treatments; one in which allows lending banks to make loan decisions knowing the health of the counter-party and the other treatment where this information is unavailable. This is very similar to the type of asymmetric situation that Akerlof discusses in the context of the used car market.

Experiment 2 shows the effect of adding a cohort of fully informed banks into an environment of no information. Said another way, there will be a group of banks that have full information about each other while the rest of the market lenders do not have information. What we expect is that the cohort may be able to increase lending in the market enough to achieve convergence. This cohort of fully informed banks would be analogous to a group of central banks or one nations highly regulated banks operating on the world market.

Finally, Experiment 3 will test the effects of changing the health limit at which banks are no longer able to repay loans. The health limit variable is interesting to test because it is a proxy for the reserve ratio. If reserve ratios are quite high, a bank does not become unstable easily and it can weather a rash of defaults or loan rejections.

Results

Experiment 1

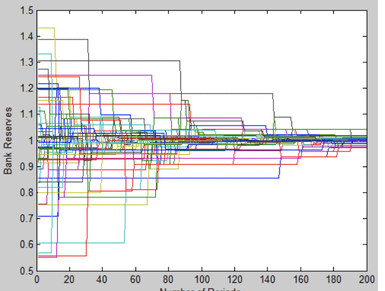

As expected from economic theory, when there is no information about bank health, a larger number of banks will be left without equilibrium reserves. Figure 1 shows that for fifty banks with no information some initial trades are possible but as loans are made to unhealthy banks their defaults decrease the health of the lenders. This means that past period 160 no new trades can be made as a large number of banks have hit the maximum level of bad health.

Figure 2 shows that with full information banks are able to get much closer to convergence because lending banks can avoid having their loans defaulted on and avoid the subsequent health penalty to the lender. Both figures use the same parameters except for information and it should be noted that some of the difference in behaviour in the early periods is a result of the stochastic matching and shock processes. Also, this result was tested for its sensitivity to changes in other parameters and it was a very general result.

Experiment 2

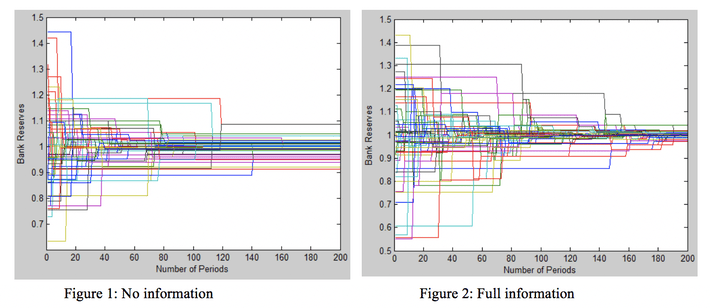

These figures explore the difference in reserve outcomes under full information and under partial asymmetric information. Figure 3 shows less convergence of reserves under partial asymmetric information than in the full information treatment shown in Figure 4.

The output array that represents the final bank health is telling in that it suggests that the banking sector is less healthy under the partial asymmetric information treatment. Because this experiment necessitate the use of specifying a partial lower triangle matrix, it was necessary to use a lower number of banks. To make sure that the results displayed were not skewed by the small number of banks the experiment was run several times for each specification and the most representative graphs were chosen for display. The general result suggests that partial asymmetric information is no substitute for full information. This experiment was important to do because the specification of parial asymmetric information reflects the state of the overnight market today. (Please see the appendix for the vision matrix specification in the partial asymmetric information treatment).

Experiment 3

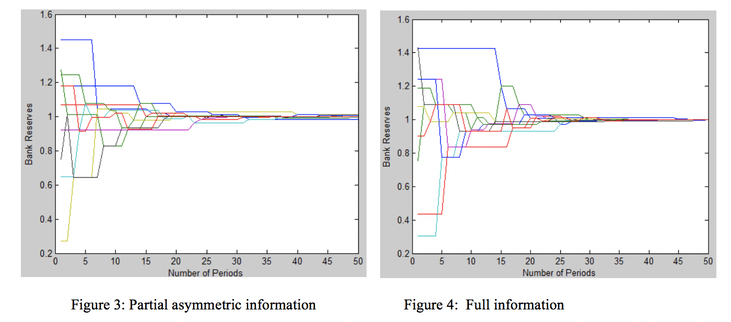

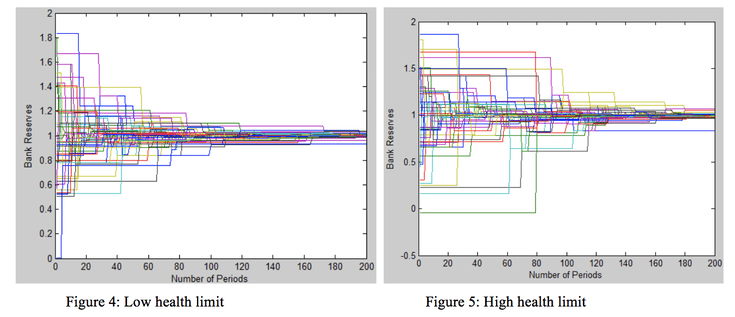

This experiment shows the differences in bank reserve convergence under two different health limits. Remembering from the computational model section, the health limit of the market is used when lending banks decide whether or not to make a loan. If the health limit is high more banks will be eligible to receive loans given that banks are operating under full information.

This experiment was done because the health limit is analogous to the required reserve level that is mandated in some countries. When required reserves are high shocks can do less to perturb the system. Even unhealthy banks may be able to rely on their own reserves rather than attempting to borrow. It should be noted that this experiment was done under full information and the high health limit, barring the single outlier, achieved better convergence. The graphs do not full convey the magnitude of difference between the two treatments because the y-axis is not symmetric. Also, the difference between the health levels in each treatment was not that large because setting very strict health limits means that few if any loans can be made and the system breaks down.

Discussion

This model is limited in that there is no explicit interest rate and that information between two banks is specified in a binary fashion. The lack of explicit interest rate should not be of particular importance because of what the asymmetric information literatures says happens when bank quality becomes exogenous. The decision to forgo an explicit interest rate was made for modelling simplicity and should not cast any major doubt on my results. The binary specification is a bit more troubling because in the real world counter party information is always known in degrees. In the 2008 financial crisis banks were trading the CDS derivatives which would mean that banks would have some idea about those holding the toxic assets. This means that while my model is not entirely externally consistent the policy suggests that come out of it are good points of departure for any regulatory debate.

This paper has shown that without full information and high reserve ratios the overnight market for loanable funds will not function correctly as we witnessed in the 2008 financial crisis. Experiment 1 and 2 showed that information about bank health can benefit all parties by making the overnight market more efficient at getting reserves to the banks that need them. If each bank has full knowledge about the health of all other banks, then any loan that is made will be paid back because lending banks only loan to healthy banks. This result would generalize to a market with a variable interest rate because as Stiglitz and Weiss (1981) suggest; when interest rates get high the only banks willing to pay them are the banks that will surely default.

Experiment 2 is particularly interesting because it is analogous to the current state of the interbank lending market. Especially in the case of Europe there are a number of major banks that do not have information about one another and a small number of central banks which have better information about the other agents in the market. What Experiment two shows is that even if the central banks have full knowledge about the health of the other major banks, which they generally do not have because of dark pool derivatives, this is not enough to avert serious freeze ups in bank trading.

Experiment 2 uses the health limit as a proxy for reserve ratios. It shows that if reserve ratios are required to be higher, the overnight market will function better in a crisis. From a policy perspective this means that the government should consider reinstituting required reserve rations that were scraped more than a decade ago in a deregulatory frenzy. Banks argue that they themselves have a stake in maintaining the correct reserves because the interest on borrowing is penalty for insufficient reserves. However, it is also true that higher profits result from the lack of minimum reserve ratios. Since this paper shows that low reserve ratios hurt not only the borrowing bank but the liquidity in the market there is an obvious negative externality associated with low unregulated reserve ratios. The government must be clear about whether banking regulation is to ensure stability or greater bank profits.

From a policy perspective it is important for all banks to have good knowledge about the risk that they face when lending to other banks. Governments must ensure that bank quality is apparent to counterparties within the market in order to keep credit moving in the event of a crisis. Since 2008, the interbank lending market has not been as liquid as it previously had been. Banks have increasingly turned to the repo market where interbank loans are collateralized by government bonds. This suggest that the central banks of the developed world can only do so much using monetary policy to make banks confident enough to lend to each other. If the high transaction costs of the repo market are to be abandoned, government policy must address the market structures that cause and perpetuate financial crisis.

Appendix

Above is the specification of the vision matrix used in the partial asymmetric information case.

Below is the MATLAB code used in the experiments:

%Information and Banking Liquidity%

%Keenan Viney%

‘Start——————————————

n=50;

vision=ones(n)

shockSize=0.2;

nShocks=300;

omega = ones(n,1)

reserves = ones(n,1);

healthLimit=50

numPeriods=200

reservePlot=zeros(numPeriods,n)

loanPlot=zeros(numPeriods,1)

%healthPlot=zeros(numPeriods,n)

for i = 1:nShocks

pair = getMatch(n)

reserves=shock(pair, reserves, shockSize)

end

mean(reserves);

for t = 1:numPeriods

%sort lenders and borrowers%

lenders = [];

borrowers;

for i = 1:n

if reserves(i)>1

lenders = [lenders i];

elseif reserves(i)<1

borrowers = [borrowers i];

end

end

pair=getTransMatch(lenders,borrowers);

if (length(lenders)>0 && lenght(borrowers)>0)

if ((vision(pair(1),pair(2)) == 0) && (omega(pair(1),1)<=healthLimit))

loan=1

else

loan=0

end

end

if loan==1

avgReserves=(reserves(pair(1))+reserves(pair(2)))/2

reserves(pair(1))=avgReserves

reserves(pair(2))=avgReserves

if omega(pair(2),1)<=healthLimit

omega(pair(1),1) = omega(pair(1),1)+1

else

omega(pair(1),1) = omega(pair(1),1)

end

else

omega(pair(1),1) = omega(pair(1),1) %repay, no health consequences%

end

else

omega(pair(2),1) = omega(pair(2),1)+1

end

end

reservePlot(t,:)=reserves;

loanPlot(t,:)=loan;

end

%Overnight Lending Functions MATLAB Script%

%Keenan Viney%

%Shock Command%

function newReserves = shock(pair, reserves, shockSize)

shockAmount = -shockSize + 2*shockSize*rand(1);

bankA = pair(1);

bankB = pair(2);

reserves(bankA) = shockAmount + reserves(bankA);

reserves(bankB) = shockAmount + reserves(bankB);

newReserves = reserves;

end

%Transaction match%

function pair = getTransactionMatch(lenders, borrowers)

pair = [0,0];

lenders

borrowers

pair(1) = lenders(randi(lenght(lenders)));

pair(2) = borrowers(randi(lenght(borrowers)));

end

%Matching%

function pair = getMatch(n);

pair = [0,0];

pair(1) = randi(n);

pair(2) = randi(n-1);

if pair(2)>=pair(1)

pair(1)=pair(1)+1;

end

%Loan Decision%

%This script is not called, it shows the structure of

%the loan decision which is nested in the Bank_sim_main file%

vision=[0 0 0 0 0; 0 0 0 0 0; 1 0 0 0 0; 1 1 0 0 0; 1 1 1 0 0]

%Lender action conditions% %line5 health must be the borrower health%

if (vision=0 || vision=1 && omega=>healthLimit)

loan = 1;

if ((vision=1) && omega=>healthLimit)

loan = 0;

%Repayment action conditions%

if loan=0

repay=1

else if loan = 1 %Vision must be called from the matrix%

if omega(pair(2), 1)>=healthLimit

repay=1

else

repay=0, omega(pair(1),1)=(omega(pair(1),1)+1)

end

end

%Health consequences lender%

if repay=1

omega = omega

if repay=0

omega = (omega)+1

References

Akerlof, G. (1970). The market for “lemons”: Quality

uncertainty and the market mechanism. The Quarterly

Journal of Economics, 83(3), 488-500.

Bodie, Z., Kane, A., Marcus, A., Perrakis, S., & Ryan, P.

(2011). Investments Toronto, ON: McGraw-Hill

Ryerson.

Stiglitz, J., & Weiss, A. (1981). Credit rationing in markets

with imperfect information. American Economic

Review, 71(3), 393-410.